- Home

- Mark Wildyr

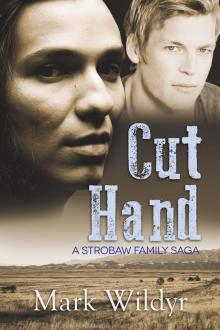

Cut Hand Page 7

Cut Hand Read online

Page 7

“Damnation, Cut, they’ve had time to plot the future of Turtle Island!”

He ignored my outburst and stunned me with his next words. “Some are questioning whether you are truly a win-tay.”

“So you finally broached the subject with your father, and they are finding excuses to keep us apart. Who’s causing the problem, Spotted Hawk?”

Cut fidgeted uneasily. “No. Lodge Pole.”

“What about people living anywhere on the Sacred Circle? What about an individual’s nature determining whether he’s a man or not? His responsibilities—”

Cut Hand laid a hand on my arm. “The responsibilities you choose are those of a man. You hunt. You fish. My father’s women clean your clothes and cook for you. You do not sew—”

“Give me a place to live, and I’ll cook and clean, by God!”

“Good. Because you must move out of the bachelors’ quarters and make a lodge like one of the People.”

“Hellfire and damnation, Cut! How am I supposed to do that?”

TO SAY my first home among the Yanube was an oddity is a vast understating of the fact. I cut and trimmed lodge poles while Butterfly and her friends prepared enough buffalo skins to make a cover. I spent a night in the open at the edge of the village nursing peeled knuckles and barked shins, surrounded by skinned poles and half-sewn hides. Otter was the only male willing to help with “women’s work,” sewing as fine a stitch with his bone needle as I did with my metal.

Cut Hand showed up after dark and endured my goosiness stoically. He eased my depression by holding me close as we lay beneath the stars. Exhausted, I fell asleep without arousing Pale Hunter, who preceded me in slumber.

The following afternoon, I raised my tipi only to have it flop back to earth in a jumble of poles and ripped skirts. Otter again came to the rescue. He showed me how to bind four poles near the top and spread them to provide support. Then we added other poles to steady the framework. He was as proud as I when the cursed thing managed to stand. By the time it was properly draped with repaired coverings, another day turned into night. It only took two days to do what any Indian wife accomplished in mere hours. Cut Hand handed out lavish compliments, ignoring the fact my lodge opened to the west when all others faced east, the First Direction. Then I learned about such things as backrests to serve as lounging chairs and parfleches to hold our goods.

It was all worth it when Cut Hand covered me in the privacy of our own lodge. He chose that night for his first act of reciprocation, lowering his head and struggling with Pale Hunter until I shuddered through an unbelievable orgasm. After that, we worked over Dark Warrior until he was scoured!

The next morning, Cut dropped the other moccasin, and the nearest neighbors sought refuge in another part of the village. “Billy, I want you to wear women’s garb. A dress, a shawl. Something!”

“What? Never!”

Eventually, we arrived at a compromise. I took to wearing bright red galluses, which some call suspenders, or a crimson belt, or brilliant garters tied to my trousers below the knees, all dyed with colors mixed by village women…. Later, I managed to acquire some crimson ferret—narrow tape that scriveners use to tie up documents—to festoon my arms. I sported something flamboyant every day. There came a time when these red men with their wry sense of humor labeled me, a white man, the Red Win-tay.

Next, I wove one of the willow frames that serve the People as chairs. Unfortunately my first attempt fell apart and dumped Cut Hand into the dirt. He had the good sense to withhold complaint.

The following morn brought a double blow. My handsome lover started the day off wrong as we broke fast.

“Can I be what?” I roared.

“You don’t need to act like a woman, just be a softer man,” he reasoned.

“Hah!” I sputtered. “I am not a womanly man, and I won’t be a womanly man. I built your bloody wigwam and dressed up like a bawdy-house madam, and if that’s not good enough, then so be it! I’ll be myself, as you instructed me in the mountains. ‘They’ll accept you if you’re just yourself, Billy. And I always tell the truth!’ Those were your words, Cut Hand, scion of the People of the Yanube!” I added as a deliberate stricture.

“I did not lie!” he protested. “I just… miscalculated.”

“Say it, Cut Hand! How did you miscalculate?”

“Men already have children before they marry win-tays,” he said hastily.

“If you think I’m going to wait until you marry and have two or three fry, you can perform an unnatural act upon yourself!”

He drew himself up proudly. “I will resolve this.”

“Is there anything else I should know?”

He shook his head firmly.

I do not believe Cut lied to me, but there was definitely something else I needed to know. A handsome man of middle years showed up and announced that he would lie with me until his wife was over her menses. He left deeply offended, not by my refusal, but from my torrent of English vulgarities.

My next visitor was a child in his teens. When I sent him packing, he swore I sounded like every shrew of an Indian woman he’d ever heard. He didn’t get half of what Cut Hand received when my love showed up for the evening meal!

When he had his fill of my ranting, he reassured me as only Cut could. Most of my anger, he understood, came from fear and uncertainty over the future.

“Why haven’t we heard, Cut? What if they don’t agree to let me stay?”

“Then we will go somewhere else.”

“You will leave your people for me?”

“As surely as you left yours for me.” He rose and held out his hand to pull me to my feet. “We will go hunting tomorrow.”

“Are win-tays permitted to hunt with the men?”

He ignored my sarcasm—as I had hunted with Cut and his friends often—and replied jauntily. “That’s one of the advantages of having such a wife. She can do your hunting for you. I can grow as lazy as a new pup with a full tummy.”

“Yes, but if you ever call me ‘she’ again, I’ll take my skinning knife to you.”

Chapter 5

THE DAYS stretched and drew out my anxiety. In a small community such as the Yanube village, privacy does not exist, yet it became clear I was being observed especially closely. Natural, Cut Hand claimed. A stranger among the band fueled curiosity.

One day an attractive matron scratched on my tipi, which I scornfully dubbed the Wacky Wigwam, and asked after some medicine in aid of her cramps. I had withdrawn to seek out something from my medicine bag when I halted in my steps. I had come within an eye’s blink of providing her laudanum before Cut’s warning about Spotted Hawk leapt to mind. Reluctantly I denied having anything to help her.

Later a young man joined me as I washed at the men’s bathing place in the river. Introducing himself as Badger, he demonstrated an uncommon curiosity about the white man’s religion. Suspecting chicanery, I guarded my tongue carefully.

“I learned of the Great Spirit from Cut Hand,” I replied, “and have come to believe he is the same as my God, Jehovah, who created all things. From what I can see, we share the same Great Mystery, although there is a difference in our creation stories. My faith teaches that the Great Spirit sent his Son, whom we call Jesus, to live among us as a man.”

Badger pursed his lips, but I could see he was not rejecting my words, so I continued.

“This Jesus is accepted as our savior. He came to earth to live and suffer among us to show us the proper way of living.”

“Hah” was Badger’s reaction to this news. That was a word liberally used to express—just about anything.

“Jesus was persecuted and slain by others because he was too perfect to live among imperfect men.”

This time his “hah” expressed disbelief. “The Creator allowed mere men to slay his son?”

“Has the Great Spirit never done anything to surprise you?”

He frowned and turned thoughtful over that one. “It is true that mortals are jealous

of perfection.”

Cut later told me Badger was Spotted Hawk’s nephew.

I crossed paths with Lodge Pole one day, giving me my first good look at the man who displayed the same grotesque form, bony features, and lumbering gait of a freak I’d seen in a sideshow during my Moorehouse days. The circus billed the man as Sampson the Invincible. But I perceived he was afflicted with something called gigantism… a weakness, not a strength.

Lodge Pole continued on his way without speaking, but he examined me obliquely, with a fierceness that was disconcerting. This was one—as my father used to say—to watch his waters, that is, a person who bears close scrutiny.

Later, when we were alone, I pressed Cut for more information on this strange man. Cut eyed me for a moment before answering.

“He has no quarrel with you,” he assured me, “but if he can use you to cause me trouble, he will do so.”

“Another little detail you neglected to mention,” I said. “Why does he wish you ill?”

“He’s ambitious. He covets my father’s place.”

My heart gave a timid leap. “Is the leadership not something you inherit?”

He shook his head slowly. “No, the People will choose their next leader. But most will look to me.”

“This is the answer!” I allowed my joy to surface. “If he wants it, let him have it. It solves our problem. The leadership can pass, leaving us free to live our own lives.”

My beloved’s sour grimace pierced my bubble of hope.

“There is a reason he does not live among his own people,” Cut said slowly. “He led a raiding party into an ambush, and some claim he deserted them to save his own hide. Others—mostly friends of his, I understand—said it wasn’t his fault. He was injured in some manner and unable to come to the aid of those he led. Whatever the truth, his own tiospaye made it uncomfortable for him, so he joined his wife’s band. I do not trust him, Billy. Yet, he has his followers, and if I do not seek the lodge before the hocoka, he might prevail.” I recalled the hocoka as the meeting place before the chieftain’s tipi.

“And that would be a catastrophe?” I knew in the bottom recesses of my heart his assessment of the giant merely confirmed my own.

“I fear it would be the end of the tiospaye,” he responded.

I thought for a moment. “It could be the threat will take care of itself. I judge him to be… what, thirty-five snows?”

“Or more.” Cut watched me intently.

“Chances are good your father will outlive him.”

His mouth dropped open in surprise. “And how do you know this? Among your other talents, can you see into a man’s future?”

“Hah,” I replied. Would it were so, I would look into my own. “No, it is his condition that foretells his future. He is afflicted with an abnormality. That is why he is so huge. Likely in his younger days he looked relatively normal, but now his bones are becoming enlarged. He walks with a jerky gait. People who suffer this malady do not normally live long. I think there is something about this in one of the traders’ medical books. We will look it up.”

We left it at that, each mulling over what he had learned.

BEAR PAW, Little Eagle, and two others joined Cut and me on one of our hunts. We were only moderately successful, as the normally curious antelope were unaccountably wary. Little Eagle claimed the sight of a white man frightened them. As we returned to the village, the buzzing of a buttoned viper spooked Bear Paw’s pony. The animal reared, and unbalanced by a pronghorn carcass slung across its crupper, went down hard, breaking Bear Paw’s right leg and sending one of the antelope prongs deep into his back.

Cut sent Little Eagle racing for Spotted Hawk, but all agreed we dare not wait for the medicine man. Cut sat behind the injured hunter and held him for me while I examined the wound in his back. No large blood vessels were punctured and his breathing seemed normal, so I allowed the wound to bleed out poisons while we tended the leg. I stood in front of Bear Paw and tried to muster a grin.

“You are not going to like me very much. This is going to hurt.”

“Don’t like you much now.” He tried to keep a light tone. “Do what you have to.” For such a big man, he looked terribly vulnerable.

“Fair enough. Hold him still,” I told the others.

Bear Paw did not utter a sound as I set the leg and bound it between two strips of wood from a nearby shrub. Then I cleaned the stab wound in his back with antiseptic from my ever-present travel kit and cauterized the injury with a heated knife blade. After this painful process, I smeared on ointment of the black poplar to succor the burn. Lastly, I bandaged Bear Paw with strips torn from my shirt and put his arm in a sling made from the remainder of it. Spotted Hawk arrived as I finished.

I worried over the old shaman’s reaction all the way to the camp. This might be precisely what Spotted Hawk needed to reject my petition. He struck me as a closed and suspicious man, although he saw to the needs of his people adequately from what I could judge.

The first thing I did on reaching the Wacky Wigwam was to dig out a spare shirt and cover my naked torso. Two messages reached me at almost the same time. I answered the summons from Spotted Hawk before I went to see Bear Paw.

The shaman invited me inside when I scratched on his tent. Entering nervously, I sat to the right of the doorway, as was expected of a polite guest. He occupied the catcu, the seat of honor. As a courtesy I endured a ritual pipe in silence, which did little to calm my anxious stomach.

“Tell me what you did before you closed his wound,” he said when our smoke was exhausted.

He sat in stony silence during the telling of my treatment, showing some curiosity about the black poplar ointment. Then he rendered his judgment. “You did well.”

Relief made me giddy but not incautious. “Thank you, but we must wait and see if the sickness sets in.”

“If it does, it was not because of what you did.” He paused a moment. “I think you will be allowed to live among us.”

I wondered if I had misjudged the old man. “Spotted Hawk, thank you for your aid. I know the decision could not have been made without your support.”

“Hah,” he said, and the interview was over.

Bear Paw was ensconced on a backrest in front of his tipi. His young wife disappeared inside as soon as I showed up. He waved me to a spot on the other end of the blanket, and I endured a second smoke I did not want.

“Thank you for helping me,” the young man said, stoically enduring the pain in his leg. His dark skin had gone even darker, and he demonstrated signs of lethargy. “Tell me the truth. If you were treating Cut Hand, would it have hurt as much?”

I laughed. “Yes, in truth, it would.”

“You did not make it harder because I have not come over to your side?”

“I do not cause pain on purpose, my friend.”

“I want you to know I am on your side now. Remember that if there is another time.”

As we both chuckled over his wit, his wife came out of the tipi and handed me a beautiful, incredibly soft and supple buckskin shirt.

“Since I am wearing yours—” Bear Paw indicated the bandage circling his broad chest. “—Half Moon thought you should have another in its place.”

PERMISSION TO stay was granted around a council fire that same evening. The tiospaye held a dance in celebration, a wild and exhilarating affair. Dances have a spiritual meaning for these people—as do most things. The big, booming drums and the piping flutes and raucous rattles stirred the blood unaccountably. For the first time I heard the men’s songs of love and war and bravery. The women’s screech-owl trill was somehow more savage and primordial than all else.

Men, resplendent in a variety of feathers—eagle, hawk, turkey, pheasant—danced together while women in dresses adorned with beads and shells and colorfully dyed porcupine quills danced apart. Occasionally, there was a social dance where everyone participated. They even prevailed upon me to shuffle along on these latter.

Once, an eagle feather came loose from a headdress and fell to the ground. Immediately everything came to a halt. Four mature men, or round bellies, approached the fallen plume from the four cardinal directions to retrieve it. Lodge Pole reverently bore the sacred feather to Spotted Hawk. After the old shaman performed a brief ceremony to restore the quill’s potent medicine, the dance resumed and continued until the early hours. Even my bed in the Wacky Wigwam looked good when I finally got there.

The next day, Cut and I gathered six of the roach-maned trace horses and set out to recover the traders’ wagon. I hoped to have him to myself for a few days, but that was not to be. Buffalo Shoulder and Little Eagle insisted on seeing the site of the Wagon Raiders Battle, as they termed the place.

They proved good and gregarious companions, although I could have done without the jugs lashed to Buffalo Shoulder’s mount. He drew from one steadily but was unfailingly generous in offering the contents to the rest of us. I took but a single swig of the bumblebee brew, yet its sting was too much for me. Cut partook sparingly; Little Eagle, liberally. I chewed on my tongue to refrain from sharing the common sense that children should not indulge in spirits. The boy could not be more than fourteen. But this was their world, not mine.

Nature and carrion animals had not been kind to the rotting carcasses of the slain raiders. Fortunately the tribesmen have an aversion to cadavers, so the curiosity exhibited by Buffalo Shoulder and Little Eagle was quickly exhausted. None too soon for me, we moved on to the Broken Wagon Ambush site.

The hidden Conestoga was serviceable with only minor repairs. I exasperated my companions by taking time to dismantle and salvage most of the second, damaged vessel. I was glad I brought six of the big horses, because the scoop wagon was heavily loaded. Once I figured out which was the hand horse, I lashed the spans in place with salvaged harness, and we set off.

Darkness fell before the wagon broke out onto the plains, so we marooned in the foothills. Cut and I slept in the Conestoga, but the others merely toppled over in place once their jug was empty. I reached for Cut as soon as everyone was settled. “I want you,” I whispered in his ear. “I had hoped we would be alone.”

Cut Hand

Cut Hand