- Home

- Mark Wildyr

Cut Hand Page 10

Cut Hand Read online

Page 10

OUR HOMESTEAD was completely finished by the time the band’s out-parties reported the buffalo herd that fall. Excited over my first hunt, I refused to listen when Cut bade me remain behind. Most of the warriors of the camp rode out ahead of the women, who followed with knives and hatchets and travois for packing the meat. The hunters were in high spirits, each describing how he would slay more of the animals than his neighbors.

What followed numbed the senses. The Indians rode their hardy little ponies into the midst of the shuffling, snorting herd to fire point-blank into the side of both bull and cow. Several of the ponderous beasts fell before the stampede started. So began the most blood-pumping, exhilarating adventure of my life—pounding alongside a wooly half-ton beast fleeing for its life while I fought to stay aboard a racing, pitching horse.

Beyond the deafening thunder of the stampeding herd, the grunts of the fleet ponies, and the yelling and cursing of the hunters, the most overwhelming impression was of smell, of powerful odors: feces, urine, intestinal gasses, blood, slobber, mucus, musty pelts, dry choking dust—and fear! Fear has its own stink, and mine was as different from Long Wind’s as his was from the huge bison bull we pursued. Drawing his breath in great, lowing gasps, the buffalo veered, almost sending Long to his knees and me beneath a thousand flying hooves.

Flouncing wildly atop my racing mount, I fired blindly, unable to take proper aim. The massive beast did not even grunt. Struggling to bring up my second rifle, I loosed a ball behind the shoulder. The mammoth beast stumbled and tumbled. Long cut to the left, away from the stampeding herd, and I saw there were yet more of the beasts behind us, blindly following the panicked dash of their brethren across the ancient trace. Fumbling to reload, I picked out a cow and ran her to death.

Done with the carnage, I hauled up and watched the dreadful spectacle with rising excitement. Rifles emptied, the Indians relied on arrows. In the span of an hourglass, fully five-score beasts littered the landscape, with groups of women hacking and hewing at the carcasses.

The hunters transferred to fresh mounts and turned over their buffalo horses to youngsters who would walk the beasts while they cooled off. The men once again became warriors and proceeded to scout the area for danger. The hunt took us a far distance from the village, and the Yanube would not be the only band engaged in such a slaughter in our vicinage.

I sat astride my gallant little pinto, allowing him to blow, and took in the tableau that stretched for miles over the prairie. Then I dismounted and began walking to allow him to recover and to consider what I observed and participated in this day.

Given that tatanka provided all of the instruments of the People’s existence, the kill today was well measured. There was sufficient meat for food to last the winter, not to mention wooly hides for tents, blankets, and clothing. Nothing would be wasted. Bones, intestines, hooves, marrow, all would be utilized. The existence of the band was assured for another season.

Cut drew alongside on Arrow and paced me. “You did well, my love.”

I looked up at him sharply. He did not often utter endearments except in the blankets. My eyes roved his excited form. Apparently a hunt such as this was as efficient an aphrodisiac as warfare. I grew aware of my own arousal.

“Cover me now!” The stimulation of the chase settled in my loins, and I tingled from every orifice.

His eyes danced. “Buffalo running is bloody work.”

“I don’t care! I’ll clean off the blood and sweat with my tongue.”

“Do you wish Butterfly and Half Moon to watch us copulate?” he asked as the two women dropped beside the carcass of a half-grown calf nearby. He laughed. “Be patient, my handsome wife. Tonight you will beg me to stop.”

“That is a promise you’d best keep!”

We were late in returning to the Mead, and he dallied with his bathing, but after that, he delivered on his promise. I required his help to the chamber pot to void my bruised bowels. I took a small measure of satisfaction the following day when he complained Dark Warrior was sore to the touch.

Chapter 7

CANADIAN NORTHERS heralded an early winter, and with the appearance of chill winds, the dress of the People changed. Buckskin leggings covered red-brown legs, soft hide shirts hid bronzed chests, and moccasins rose to the knee. Coats and robes and body blankets draped broad, muscled shoulders. My deviancy apparently now clasped me in a firm grip, as I frankly preferred the summer months, when the men’s habit usually consisted solely of loincloths. Although tempted by none beyond my ability to resist, there was nothing to prevent me from enjoying the sight of such flagrant masculinity. I knew full well that Cut peeked down a maidenly bosom on more than one occasion.

We decided to accompany the People on their trek south to haul the heavier provisions in the Conestoga. This was my first move to winter quarters, and the epic of an entire town traveling across the plains with the precision of long practice proved a novel experience. Moccasins and hooves and travois poles tore a wide track across plains littered with horse apples and dog date and the occasional human offal when some child could wait no longer. Plodding mounts, seemingly resigned to a long trail, bore the young and the ancient and sleds containing household goods. Decorated umbrellas of buffalo hide, stretched over bone or wood poles, sheltered men and women alike from the still-potent autumn sun. The spare horses, herded by boys and young men, traveled to the west of the column to avoid the lung-clogging dust.

Even the dogs labored on behalf of the People, hauling a load, sometimes in a pack, sometimes on a miniature travois. Only the pups—human and canine—ran free, yipping and yelling and laughing and crying, nipping at fetlocks or tugging at skirts. Toddlers made some portion of the journey on short, stubby legs supported by leading strings firmly held by sisters or aunts. The smallest rode strapped into cradleboards on their mothers’ backs, viewing the retreating world through huge dark eyes.

Cut Hand and his Porcupines rode wide circles around the lengthening column to scout danger, lend assistance, and hurry along stragglers. I rode drag in the Conestoga.

The journey was to take four sleeps, which calculated to around a hundred and twenty miles. Excitement gave way to drudgery ere the first day saw its close. To break the monotony, I invited Butterfly to share my seat and bring me up-to-date on her life. She had dropped out of our circle of regulars at the Mead. As neither Cut nor I understood the reason, I asked her plain out as we rolled across the prairie avoiding ha-has, those hidden gullies that unexpectedly cut the rolling countryside.

“I could not handle all the happiness.” She gave voice to this enigmatic answer and then firmly shut her lips.

Butterfly no sooner abandoned me to solitary travel than a gruff voice requested permission to ride a distance. Startled, I beheld Lodge Pole at my off-wheel. Waving him aboard, I prepared to halt the team, but he accomplished the transfer from horseback to wagon seat on the move with only mild awkwardness, using strength in the stead of grace and balance. The slat beneath my bum buckled alarmingly as he settled his great weight.

I cast an eye on his mount, curious as to the beast that handled such bulk. The horse was a bosomy, puddle-footed draft animal fully eighteen hands high with short, wide hindquarters and a broad back, the antithesis of the usual plains pony, which was bred for speed and stamina.

“Greetings, Teacher. Thank you for allowing me to rest my weary bones,” he boomed.

I laughed. “Hold your thanks a league or two. This contraption is more apt to rattle bones than give them rest.”

“True,” he acknowledged, his teeth clacking audibly. “But the agitation is to different parts of the body.”

To my surprise, the big man was a pleasant companion. He gossiped easily about the tiospaye, giving me insights into several individuals. I gained the impression he was as well-informed as Yellow Puma and Spotted Hawk. After a time, I began to relax, which was doubtless his intent.

“I was baffled by Cut Hand’s defense of Buffalo Shoulder,” he said

out of the blue, watching me closely. “Although I suppose it was no surprise to you.”

My eyebrows shot up so forcefully they shoved the hat back on my head. “How so?”

“Were you not the one who wished him to remain?”

“Me!” I seemed stuck on monosyllables. “Why do you think that?”

“Buffalo Shoulder is a handsome man… personable,” he added, perhaps intending to soften the stricture.

“Handsome young men or clumsy old giants,” I spewed before my mind wrapped itself around things and controlled my tongue, “dereliction of duty resulting in the death of anyone merits punishment.” Abashed at my effrontery, I glanced at him and was repulsed by the enlarged, bony features. He no longer seemed presentable company. “Lodge Pole,” I blathered on, “let’s understand this thing clearly. Cut Hand does not consult me on matters of the tiospaye.”

He pursed thick lips. “Strange. Was not your counsel to be of such value when you petitioned to remain?”

Unfortunately I am a fair-skinned man who shows his condition. I felt my cheeks flaring. “In matters relating to the Americans, he learns from me. In matters of the People, I learn from him.”

As much as I desired it, I dared not order him from the wagon. He held too much standing in the community to be treated rudely. No matter; having taken my measure, he was prepared to leave. I halted the wagon while he negotiated a transfer in the reverse.

The days passed slowly, and I saw little of my mate even during the night, but eventually the band reached its destination without undue difficulty. I gaped in awe at the efficiency of the women as they erected their tipis. Within hours, the village looked as if it had sat in that very spot for years. Other bands arrived to add lodges to those already standing. Cut and I intended to sleep in the wagon.

I found a quiet moment as we stood aside from others at the edge of a small grove of trees to relate my encounter with Lodge Pole—almost to my regret. Incensed, Cut Hand was well on the way to confronting the giant before I convinced him that was exactly what the man wanted. Frustrated, my love hacked at a poplar with his knife as if assaulting his nemesis.

“He is a pimp! He cannot talk to a man’s wife like that!”

“He knows I’m not a traditional wife. He’ll claim that fact to excuse his boldness. Damnation, Cut, many take liberties with me they wouldn’t dare with a woman.”

He turned to face me squarely, and I read the thoughts behind those magnificent eyes.

“It cannot be helped,” I said, spreading my hands and shrugging. “I am who I am, and I behave according to my nature.”

He relented. “And I would have you no other way. So what do we do about Lodge Pole?”

“Ignore him. That will injure him more than anything. But this is only his opening salvo. He may begin starting rumors.”

My outraged love breathed dragon’s fire. “I’ll kill him if he does!”

“We’ll figure out what to do when the time comes. Just promise me one thing. Don’t let him drive a wedge between us.”

“No one will ever do that!” my mate cried, clutching my shoulders and drawing me to his breast. As there were others within sight, he released me quickly.

Although Cut determined to stay with the tiospaye a few days, I insisted on returning home. He argued but stopped short of forbidding me to go, possibly because he reasoned it might carry an afterclap, a consequence. To avoid a series of brutal gullies requiring long detours, I followed the south bank of the Yanube to commence my journey.

I do not know how long the warrior paced me to the west before I finally spotted him. Woolgathering about Butterfly’s mysterious attitude and Lodge Pole’s slur robbed me of the alertness so essential in this country. Three others rode at some distance behind the wagon. When three appeared in front of me, I hauled up on the reins. The river was to my right with no walking place or ford within eyesight. I was totally cut off. Deciding to make a run for it rather than surrender to fate, I slapped the reins and urged the hand horse to action.

The wagon slowly gathered speed. Gambling they would not shoot the horses, I scattered the three braves in front of me. The warriors let out whoops of joy and fired shots into the air, anticipating the sport of the chase. The fastest mount belonged to a man who immediately lost his grip on the tailgate when I deliberately swerved to the left. My leap of satisfaction was short-lived. When I topped the next rise, it looked as if the whole Sioux Nation blocked my way. I hauled back on the reins, deciding the time to outrun trouble had passed. Now it was time to talk.

The big Conestoga clattered to a stop a hundred paces from the nearest Indian. He immediately held up a hand, and those pursuing me drew to a halt. I remained seated as a solitary figure urged his horse into a walk. Had I stood, I likely would have stained my britches, and that would be both unseemly and dangerous. There was nothing these people disdained more than a coward. These were not Sioux, I decided. They were Pipe Stem. Recognizing the approaching man as Carcajou gave me no clue as to whether this encounter was promising or foreboding.

“Hau, Teacher,” the Pipe Stem scion gave a solemn greeting as he drew up beside the wagon.

“Hau, Carcajou. How is your medicine man?”

“Come see for yourself,” he said, beckoning a rider forward. The brave exchanged places, taking the reins of the wagon while I claimed his pony.

The entire band, which looked to be larger than the Yanube, ranged across the plains on its journey to winter quarters on the south side of the river. The column halted as we neared. I knew without being told the tall man riding beside a travois was Great Bull. As we neared, Carcajou motioned me to wait while he rode forward to speak with his father. The older man signaled me to approach.

Great Bull had seen more snows than Yellow Puma but was every bit as impressive. Authority rode his shoulders like an aura. “So you are the great Red Win-tay,” he said. These people were given to hyperbole as well as dry humor, and I was helpless to determine which this represented.

“I am William Joseph Strobaw,” I intoned, proving I could pontificate too. “I am on the way to my home at Teacher’s Mead.”

He turned to an old man strapped to a horse-drawn sled made of two trailing lodge poles spanned by buffalo robes. The patient looked amazingly like Spotted Hawk. “This is Small Horse, our shaman. Your medicine is helping him mend, and your kill-the-pain drink eased his way.”

The small, wrinkled man gazed at me through squinted eyes. For something to contribute, I said I wished there was more of the laudanum.

“It was enough,” the old shaman wheezed.

“Good,” I answered inanely. Had it not been for the inherent danger, this would have seemed a hazy dream.

“Your land boat is here,” Great Bull said, pointing behind me with his chin. “You are free to go on your way.”

“Great Bull,” I said, prompted by a sudden urge. “If I visit the village of the Pipe Stem after the winter snows are gone, will I be welcome?”

He considered the question for some time before replying. “It would be better to remain with your Yanube friends.” He urged his pony forward, leaving Carcajou to oversee my repossession of the wagon and safe conduct through the remainder of his column.

Now that the danger was past, I silently acknowledged the strong sexual attraction I felt for the striking warrior who rode beside my near wheel. Immediately I was shot through with a sensation of treachery.

I crossed to the north side of the Yanube and gained the safety of my home three days later without further incident. The dogs and the horses were glad to see me. I unhitched the team, pitched fresh hay to the animals, and fell into bed exhausted—mentally and physically.

CUT RETURNED home two days after my arrival, smashing the north cavern door to enter by way of the secret tunnel. He had followed my tracks and understood I had been captured. He knew the Conestoga returned to the Mead, but who was in the wagon? The dogs’ calm demeanor led him to believe I was in the house, but was I alone?

He first expressed relief at finding me safe before growing angry because I ignored his wishes and returned without him.

He relented somewhat after I explained what happened but continued to withhold his pardon until we replaced the smashed door to the cave with one twice as strong. He now realized the value of the secret entrance.

“You are a strange win-tay,” he said, not for the first time, as he drew me to him that night. “You disobey your husband in front of the whole family, kill more of the enemy than he has, confront the entire Pipe Stem band, and walk away without harm or loss. And still your husband loves you.”

He seldom referred to himself as my husband. “Your win-tay wife loves you too, husband,” I replied in kind.

“You show it in peculiar ways.”

“I’ll show it now in ways even a dolt can understand,” I whispered and moved down to his pipe.

Our personal relationship restored, we settled in for a long winter. Cut worked hard on his reading and writing and developed a clear, running hand. Once able to understand how full and complete sentences were structured, he applied this to conversational English. Soon he would be better at my language than I was at his. We also took up ciphering so that in future dealings with traders he could not easily be cheated.

Cut paid me due attention during the cold months, leaping me frequently and on occasion accepting my seed in reciprocation by way of apology after a particularly tense day. I loved him without reserve, regardless of his mood.

We had to rescue one of the dogs shortly before the snowmelt began. The wolf pack chased West—we’d named them for the territory they patrolled—onto the stoop of the house. We put three of the dogs in the barn with the stock and took South, our favorite, into the house with us. He was a big brindle that looked ferocious even when he was lying on his back slobbering over a good belly rub.

Yet, by the tail end of this winter season, Cut was more testy than the previous year, likely because the band was at a more distant remove. He was also concerned over Yellow Puma, who suffered from a lingering ague during the move south.

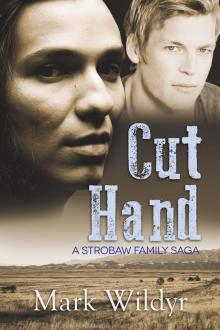

Cut Hand

Cut Hand